Species Selection for Tree Planting Projects in Canada

Introduction

What really goes into selecting the right species for the right site in a tree planting project? The answer: It depends on many factors. Naturally, species selection can become routine if you repeatedly undertake similar projects. However, even experienced companies should return to basics when it comes to species selection. It’s crucial to keep up with climate change trends and solutions for species adaptation.

What are we restoring this for?

Every successful tree planting project starts with a fundamental question: Why are we restoring this land? Species selection isn’t just about choosing what’s available or preferred species—it’s a matter of aligning the tree species with the landowner’s vision, the landscape, and the broader ecological or cultural goals. Whether the project aims to enhance biodiversity, create habitat, restore forest cover, or generate future income, the selected species must support the desired outcome.

This means asking yourself the following questions:

- Who is the landowner or client?

- What is the desired outcome for the project?

- What is the capacity for post-planting care and management?

- How do cultural values, traditional uses, or community priorities shape the desired outcome?

From here, planting projects can take off in many directions. Species selection is a ground-up process. So, before you decide what to plant, decide what you’re planting for.

Understanding the client and defining objectives

All landowners vary in their objectives for their property, as well as in their physical capabilities, skills, experience, and long-term plans. For this reason, the importance of in-depth communication with landowners before planning a project cannot be overstated. When planting for biodiversity, your options are more flexible, and you’re welcome to use a variety of different species that complement each other, including shrubs and forbs that will enhance the establishment of the forest. If the trees will receive limited or no post-planting maintenance in the future, include this factor in your planting plan. Furthermore, choose tree species with the best chance of thriving against the competition, or discuss options for hiring help. For example, hardwoods typically require more site preparation and tending after planting than conifers, so this reality will affect your species selection. Likewise, if chemical herbicides are not used, this will also influence the tree species that can be planted (i.e., work with the competition present).

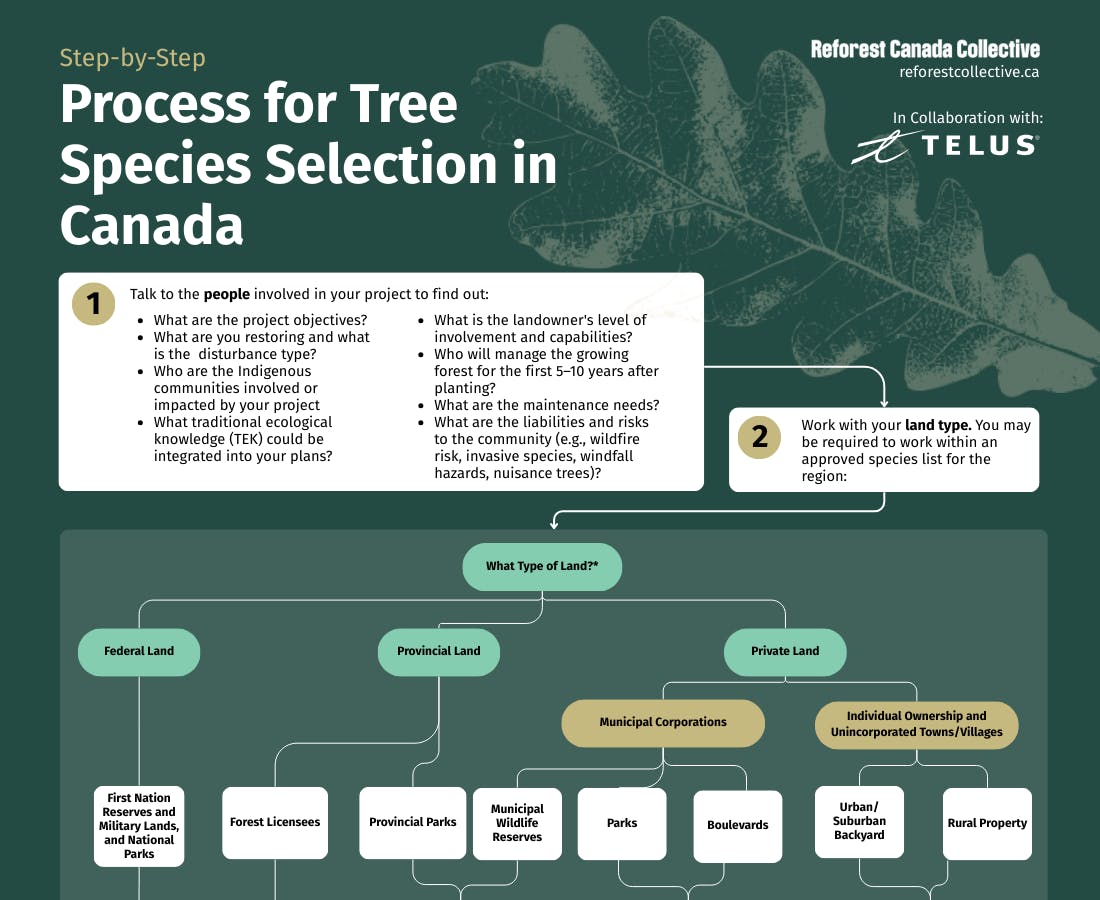

Working with the land type

Although this article focuses primarily on private land tree planting, it’s worthwhile to briefly outline what goes into planting trees on public land, namely for industry and reclamation. In the forestry sector, registered professional foresters (RPFs) conducting projects under public land forest licenses (e.g., forest management agreements [FMAs] in Alberta) select commercially important timber tree species based on land classification and regulations. The process varies from province to province. In the reclamation sector, meanwhile, species selection is usually done by environmental consultants who often have more freedom to plant species that are not always considered merchantable. In these cases, the intention is to meet environmental policies geared toward returning the forest to its original state before any development or disturbance occurred. If reclamation requirements are met, a reclamation certificate is issued, and the project is complete.

On private and Indigenous land, the variety of species selection possibilities is even broader. Ultimately, private landowners have more flexibility in steering the outcome toward their own objectives—whether they aim to restore historical forest cover, contribute to habitat, enhance their living conditions by planting trees, or develop a product or service using the land. Project developers who serve as agents for achieving corporate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) targets often select species that will produce significant environmental benefits while meeting the landowner's tree-planting objectives. For these projects, the forest is typically established with long-term conservation and environmental goals in focus, rather than commercial value.

Land classification system in Canada

We can’t talk about species selection without addressing how land is classified in Canada. Generally, ecosites are derived from ecozone, ecoprovince, ecoregion, and ecodistrict according to Canada’s Ecological Land Classification (ELC) system, which describes land with similar enduring physical attributes. For example, the Boreal Plains ecozone comprises three ecoprovinces that break down into ecoregions, ecodistricts, and ecosites. Generally speaking, the Boreal Plains ecozone is suitable for white and black spruce, jack pine, tamarack, white birch, trembling aspen, and balsam poplar. Going one step further, the ecodistrict will provide the most detailed information on species occurrences based on soil and other physical features for the area.

The Forest Ecosystem Classification (FEC) system has also been used to varying degrees across the country as a stand-level extension of the ELC system to describe ecological characteristics in a forest stand that will help guide management. In practice, they arrive at the same ecosite description. Some provinces will have their own ecozone classification system, such as British Columbia’s biogeoclimatic zones.

Start with the ecoregions, or whichever is the largest land classification level for the province you’re working in, for a specific list of species known to perform well after planting for the region. Based on the various knowledge systems in a given region, certain species are likely known to thrive when planted. Having that list of regional species options with you before your site visit is essential so you can keep your mind open to all possibilities.

As you go from the ecoregion to the local environments, your species list will get smaller and smaller. Finally, your site visit will further narrow your final list of suitable species. Keep in mind that nursery availability varies across the country, so it’s wise to assess species suitability for your site from the full suite of options first and determine which ones are most likely to succeed at the site given the conditions. Then, categorize them as your first, second, and third choices in case of shortages or lower inventory of certain species. This approach is useful to ensure you consider all options ahead of time.

Ecological succession

When selecting species, pay attention to the natural regeneration patterns on similar sites in the region you’re working in. For example, what happens to the site after a disturbance if left untouched? One of the best ways to understand which species are best suited to a particular area is to stay attuned to the many factors that promote strong forest establishment and identify common patterns.

Technically speaking, when you’re planting trees, you should be emulating the natural process of how pioneer species colonize and establish on a site, but this may not always be the case in a practical sense. For instance, many projects can include planting late-successional, shade-tolerant species with great success with the proper prescription and maintenance plan.

White pine, white spruce, and oaks are three examples of mid- to late-successional tree species commonly used in reforestation projects in Canada. Because these are not pioneer species, they may grow more slowly in open fields. Nevertheless, one benefit to using late-successional, shade-tolerant species is that your future forest already has a head start on including a diversity of species that will be found in the area. Indeed, you are accelerating the forest establishment process and helping to ensure its future trajectory.

Site-specific considerations

Going for a walk in the forest and remaining attentive to the trees that have established naturally—with or without human influence—is particularly useful. An inquisitive stroll through the prospective site can provide a lot of information on which trees will readily grow there. First, you’ll want to pay special attention to what grows in higher, well-drained areas, as well as in lower areas that are prone to seasonal flooding. Second, you’ll want to try to understand why each specific species is doing well in those areas.

We can see trees as indicators that tell us a lot about the growing conditions (beyond moisture content) that exist both above and below the surface. In Northern Alberta, for example, the main deciduous trees are aspen and balsam poplar, whose presence on a site can tell us a great deal. For instance, aspen growing on a site generally points to leaner soil (more mineral soil, less organic). In comparison, the prevalence of balsam poplar indicates richer soil (more organic matter mixed with mineral soil). Walking through the site allows us to see what species are naturally present. It also enables us to make a plan to collect seed and other plant material that can be used to propagate trees for the prospective site.

Ordering nursery stock

Once the ideal quantity and combination of species for a site have been determined, the next step is to contact the local nurseries to identify availability, what they can source, and what they can grow (if you choose to collect and provide seed to them). You will also want to check with the provincial seed banks, where you can usually find commercially valuable species, such as spruce, pine, and fir, in large quantities. Non-commercially valuable “specialty” species are not as readily available. In this case, we must either adjust the site allocations or have suitable seed collected. That said, it's worth mentioning that undertaking customized seed collection can be challenging. Moreover, having that seed grown into planting stock may also present significant timing issues.

It’s essential to research the propagation methods of the different ideal species to identify the best options. Some species are readily available as seed, some can be collected with little to no risk, and others can be grown from genetic material. With time, patience, persistence, and access to resources, we can find creative ways to develop procedures to produce the ideal planting stock for almost any species.

Seed collection opportunities

Although the timing for collecting seed and plant material varies widely, it’s worth noting that these opportunities often exist near the planting site. For example, if we want to plant a species that is difficult to source but occurs on or near the site, we can harvest the seeds locally and produce perfectly adapted planting stock. Every tree has its own season and method for seed collection and propagation. It’s a vast topic with many intricacies, but it is also one of the most natural processes, with deep cultural roots.

We can learn to collect seed ourselves, hire local community members, or find a specialized organization to offer expertise. In any case, it’s an important element to complete the most basic natural cycle: reproduction. As stated earlier, the process of allocating trees on Crown land requires that proper protocols be followed and seeds be registered with the provincial government.

White spruce cones collected during a mast year (every 5–7 years)

Some species produce seed inconsistently in terms of interval and quantity, or the harvest window can be very small. White spruce, for example, is an inconsistent species that typically produces seed in mast years (every 5–7 years), characterized by periodic events of high seed production as a natural response to environmental influences. Since white spruce is commonly used as a commercially valuable tree in the forest industry, large collections are carried out during mast years and stored in seed banks for annual propagation. Another popular species, particularly for ESG-centred planting projects on private land, is balsam poplar. This species tends to produce seed inconsistently and can pose challenges with seed storage. Due to the seed's shorter shelf life, the species is propagated from first-year cuttings taken during the dormant season. These cuttings are then rooted in a soil plug and planted out in the summer or fall.

Shakti Tree Map

While on the subject of seed collection, it’s worth noting that Shakti by TELUS has developed an in-house interactive feature, the Shakti Tree Map, based on the Government of Alberta’s seed zone map. The tool was created to facilitate the planning and allocation of trees grown from native (Stream 1, typically collected from wild, naturally occurring trees from the same seedzone as the planting site) and orchard (Stream 2, produced in “improved” seed orchards from plantations of selected trees managed for seed production) seed across Alberta. The feature allows users to search sites based on GPS coordinates or the Alberta Township System (ATS) to select the seed zone layer and choose their base map. It offers many options to make selecting the right seed source straightforward.

Incorporating local and Indigenous knowledge

When questions arise about species selection, stock type or seed collection methods, we often seek local and diverse sources of professional, Indigenous, or traditional ecological knowledge (TEK). Local farmers, for instance, are immersed in their environment and can offer insights into species performance that are often more reliable than those from a single site visit. Likewise, forestry professionals spend their time walking in the forest and often have in-depth expertise to offer on how to combine different forest elements for the local region.

Indigenous knowledge is rooted in a spiritual and reciprocal connection to the land and has always been an incredible resource for understanding forest ecosystem relationships. Consulting Indigenous knowledge holders about species selection offers valuable insights. This expertise can help determine how to best combine elements of the future forest. The role of trees is also deeply rooted in Indigenous storytelling and other oral traditions. Often, the motivation to plant trees is tied to ceremony and cultural relationships, rather than just improving the physical features of the environment. In these systems, different types of trees, plants, and animals are interrelated and connect the ecosystem as a whole. The offerings provided by the land to the community are respected and given thanks for at a level deeper than Western worldviews on resource management.

Consulting Indigenous knowledge holders about their relationship with the forest can initiate a long-lasting partnership. Knowledge holders want forests and landscapes to remain productive and sustainable for their culture, traditions, and livelihoods. Providing opportunities for meaningful input for tree species selection in tree planting projects may also lead to other benefits and opportunities towards planning, execution (planting), and long-term management of the project.

Invasive Species and Species at Risk

When selecting species for a site, also be mindful of trees listed on an invasive species list. Also consider those known by local experts to spread into neighbouring plant communities. Similar to consulting local knowledge holders for determining the species that will perform the best for a given site, it’s also imperative to consult local Indigenous knowledge holders, farmers, foresters, land managers and other stakeholders about the habits of a given species, e.g., how they establish in a plant community and whether they exhibit invasive or weedy habits. Staying up to date on provincial invasive species lists and registries is an excellent idea in addition to having these conversations with local community members to make the best species selection decisions.

Historically, non-native species were planted across Canada as ornamental trees or in an effort to overcome poor environmental conditions such as soil structure loss and desertification. Some introduced species have become naturalized and do not pose a risk to local ecosystems (e.g. Norway spruce has been widely naturalized in Ontario), but others became invasive and spread into nearby native environments threatening the ecosystem health of the region. Speak to a local forester or traditional knowledge keepers in the area about whether a particular non-native species has an invasive habit in that area before introducing it to the ecosystem. For more information on invasive species for the area you’re planting trees, consult the local government and NGO resources. The Canadian Coalition for Invasive Plant Regulation (CCIPR) provides comprehensive Canadian Invasive Plant Lists wherein you can reference provincial resources for invasive species.

If you are planning to integrate a species-at-risk into your planting prescription, be sure to consult the recovery strategy for that particular species. Ensuring the provenance and quality of seed used in the establishment of species-at-risk is important so that the population is being supported according to best practices.

Conclusion

Selecting the right tree species for planting projects in Canada is a multifaceted process—one that requires careful consideration of factors such as land classification, ecological succession, and site-specific factors. Sound ecological principles, sustainability, and the specific goals of the landowner or organization must always guide the planning process.

By following a structured approach—starting with understanding the site and ecological history, incorporating Indigenous and local knowledge, considering nursery stock availability, and planning for future maintenance—tree planting projects can create resilient, diverse, and sustainable forests. The use of seed zone maps and natural regeneration patterns further support species selection, ensuring that trees are adapted to their planting sites and can thrive with minimal intervention.

Finally, given the complexities of climate change and the many factors at play, the “right tree, right place” adage is now highly context- and region-dependent. Much of what we do as tree planting professionals involves trial and error, but with the right tools and the right local knowledge, we can maximize the chances of a successful planting project.